Woolley's Excavations

Leonard Woolley saw with the eye of imagination: the place was as real to him as it had been in 1500 BC, or a few thousand years earlier. Wherever he happened to be, he could make it come alive. While he was speaking I felt in my mind no doubt whatever that the house on the corner had been Abraham's. It was his reconstruction of the past and he believed in it, and anyone who listened to him believed in it also.

When the British Museum and Penn Museum formed a partnership to excavate at Ur, they chose Charles Leonard Woolley to head the excavations. Woolley had worked for the University Museum in Nubia and Italy in 1910, and for the British Museum at Carchemish just prior to and immediately after World War I.

At Ur, Woolley worked on a grand scale, in an era of “big digs” that no longer exists. His landmark excavations would become the largest in Iraq’s history, with seasons normally lasting four months a year and utilizing up to 300 workmen at one point, alongside a very small archaeological staff.

Woolley exhumed thousands of bodies, thousands of texts, and tens of thousands of registered artifacts. He took over 2,000 photographs and wrote nearly 20,000 pages of notes, not including letters and reports. He investigated the massive ziggurat and uncovered temples, administrative buildings, and private houses from a range of time periods, as well as royal and private graves. His excavations revealed more about Ur than we know of most other Mesopotamian cities.

Perhaps no excavation in the more than 150 years of archaeological work in Mesopotamia has excited as much public attention as Woolley’s work at ancient Ur in the 1920s and early 1930s. In the twelve years of excavations, newspapers around the world printed countless articles. Woolley often linked his finds to Biblical stories, continuing to spark public interest in Ur. The Illustrated London News ran some thirty features on the excavations, rivaled only by the discovery of the intact tomb of Tutankhamun. In contrast to that famous Egyptian find, however, Woolley uncovered and examined more than 2,000 burials. Some of them were so richly furnished as to require him to telegram the news of their discovery in secret code. As a result of the extensive publicity, Iraqis and tourists from all parts of the globe, including European royalty and even the author Agatha Christie, flocked to the remote site in the Iraqi desert.

As the Great Depression settled in it became more difficult to fund excavations and Woolley brought the work to a close in 1934. The artifacts and records were divided among Baghdad, London, and Philadelphia as agreed. The artifacts portioned to Baghdad were the first material accessioned into the Iraq National Museum. The excavation of Ur was conducted in a period of great importance to the modern Middle East, a period that saw the creation of many new nations in the region, including Iraq itself.

Important Finds

Public buildings and ziggurat

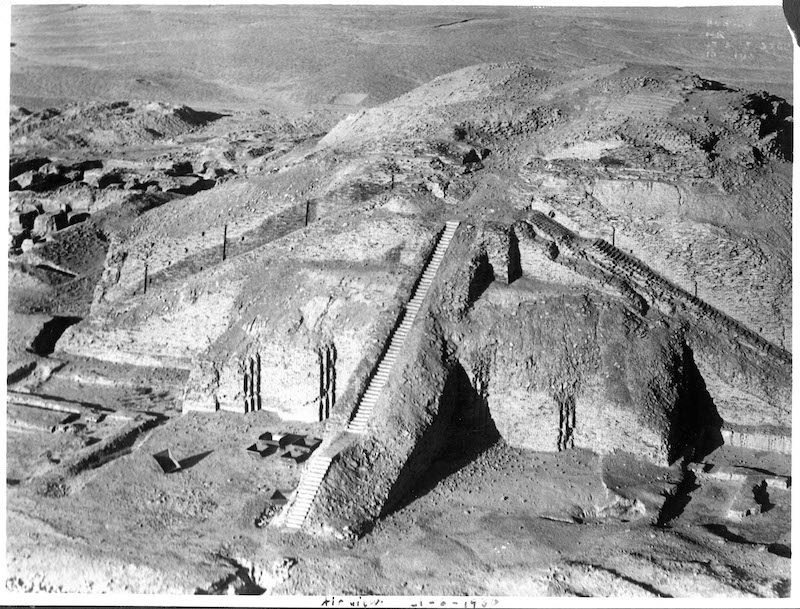

The ziggurat (temple tower) is the most prominent feature of the site. Built by Urnamma and finished by his son Shulgi around the late 3rd and early 2nd millennia BCE and rebuilt by Nabonidus 1,500 years later, Ur’s ziggurat remains the best-preserved temple tower in Iraq. A temple to Nanna, the moon god, would have stood atop the ziggurat. The ziggurat was made of a mud brick core and covered in baked bricks laid in bitumen; Nabonidus likely painted the façade black after he rebuilt it.

Other public buildings at Ur include the enunmah/ganunmah, a large brick storehouse that may later have become a temple; the giparu, a temple to Ningal (wife of Nanna) and residence and burial place of the entu-priestesses to the moon god, probably built by the entu-priestess En-ana-tuma; the ehursag, a modest square building that may be a palace; the edublamah, a two-roomed gateway at the eastern corner of the ziggurat terrace where justice was administered; and the remains of a temple built by Shulgi and dedicated to Nimin-tabba, a goddess closely associated with Nanna.

Woolley determined that the ziggurat and other public buildings were located within an enclosure or temenos. Urnamma built the first enclosure, then Nebuchadnezzar II built a larger mud brick enclosure wall, the temenos, with six gates.

Private houses

While Woolley excavated significant public buildings, he also made uniquely important discoveries about Ur’s private houses. The best-preserved private houses he discovered date to the 2nd millennium. Houses at Ur generally lay along winding streets and alleyways rather than a squared city grid. The floors of these houses were typically much lower than street level—up to a meter lower—because rubbish and dirt accumulated so quickly in the streets. Woolley noted an interesting detail: where streets met, the corners of buildings were usually rounded. He suggested this was to prevent pack mules from catching their loads on edges and knocking their wares into the street. Many crossroads also had a small public shrine or chapel.

As well as houses within the city, Woolley also found house remains outside the city walls, scattered all the way to Tell al-Ubaid, 6km to the northwest. Even in ancient times suburban sprawl seems to have been a phenomenon associated with major cities.

Royal tombs

The Ur excavations are a remarkable story, and Woolley’s prize find, the Early Dynastic Royal Cemetery, is one of the greatest archaeological discoveries ever made. In the late 1920s, Woolley uncovered a cemetery with as many as 2000 burials spread over an area approximately 70 by 55 meters. Of these, Woolley assigned 660 burials to the Early Dynastic Royal Cemetery, from the middle of the 3rd millennium BCE. Most of these were relatively simple burials, but Woolley noted that 16 stood apart from the rest. He assumed that they contained the remains of Ur’s kings and queens, so he called them “royal tombs.”

These royal tombs consisted of a vaulted or domed stone chamber set at the bottom of a deep pit and accessed by a ramp. The principal body lay in the chamber, buried with substantial quantities of goods and objects made of semiprecious stones, gold, and silver, sometimes including a sled or wheeled vehicle pulled by oxen or equids. Personal and household attendants lay in the tomb chamber with the deceased king or queen and in the pit outside, which Woolley consequently termed the “death pit.”

Woolley imagined what had happened after the deaths of Ur’s kings and queens as follows:

We must imagine the burial in the chamber to be complete and the door sealed; there remains the open pit with its mat-lined walls and mat-covered floor, empty and unfurnished. Now down the sloping passage comes a procession of people, the members of the court, soldiers, men-servants, and women, the latter in all their finery of brightly colored garments and headdresses of lapis-lazuli and silver and gold, and with them musicians bearing harps or lyres, cymbals, and sistra; they take up their positions in the farther part of the pit and then there are driven or backed down the slope the chariots drawn by oxen or by asses, the drivers in the cars, the grooms holding the heads of the draught animals, and these too are marshaled in the pit. Each man and woman brought a little cup of clay or stone or metal, the only equipment required for the rite that was to follow. Some kind of service there must have been at the bottom of the shaft, at least it is evident that the musicians played up to the last, and that each drank from the cup; either they brought the potion with them or they found it prepared for them on the spot—in PG 1237 there was in the middle of the pit a great copper pot into which they could have dipped—and they composed themselves for death. Then someone came down and killed the animals and perhaps arranged the drugged bodies, and when that was done earth was flung from above on them, and the filling-in of the grave shaft was begun.

Many mysteries about the royal tombs and death pits remain. Did the ritual happen as Woolley imagined? Or did royal attendants go to their deaths less willingly? Why do some death pits include only a handful of bodies while others contain far more, like the 73 retainers (5 men and 68 women) in the “Great Death Pit” (PG 1237)?

Some of the royal tombs uncovered by Woolley had been partially destroyed, probably when later tombs were dug. Nearly all of the royal tombs had been robbed in antiquity but some still contained their riches. For instance, in PG 800, the royal tomb of Queen Puabi, Woolley uncovered her fabulous gold headdress and burial attire beaded with semi-precious stones. Woolley’s finds were so incredible, so rich, that he wrote telegrams to British Museum and Penn Museum directors Kenyon and Gordon announcing these spectacular finds in Latin so the news would not be intercepted.

The excavation of these royal tombs was no easy task. The soil into which the tombs were cut was composed of dumped rubbish which was not only soft and unstable but also acidic and highly salinated with the result that it ate away at skeletal remains. Woolley’s recovery of artifacts from the cemetery’s royal tombs still stands as an extraordinary technical achievement, all the more remarkable when one realizes that Woolley and his wife, Katharine, or one other assistant did all the detailed digging themselves.

Prehistory

In the digging season from 1928 to 1929, after Woolley had excavated part of the cemetery to a depth of 10 to 13 meters, Woolley decided to dig below the floor levels of the excavated burials. He made a startling discovery: a thick layer of water-laid silt indicative of flooding on top of a layer containing characteristic black-painted pottery of the Ubaid period, the earliest phase of occupation on the southern Mesopotamian floodplain. What did this mean? In some of his publications Woolley connected this deep layer of silt to the Biblical flood, which may also be alluded to in the Sumerian King List.

Field Seasons

First phase

Woolley started his excavations at Ur in early November 1922. After digging two initial trial trenches, Woolley spent his first five digging seasons focusing on the high mound with its ziggurat and public buildings within Nebuchadnezzar’s temenos (enclosure wall).

Second phase

In the second half of the 1920s, Woolley shifted his primary focus to the cemetery. In less than three months in 1927, he uncovered some 600 burials, including one rich tomb (PG 580) that contained a many gold implements. In the next two seasons he uncovered hundreds of additional burials: 454 in 1928-1929 (including PG 755, PG 789, and PG 800) and 350 in 1929-1930 (including PG 1237, the so-called Great Death Pit).

Third phase

In the last few seasons, Woolley focused on investigating the pre-history of Ur, with the silt flood layer. His last season ended in February 1934.